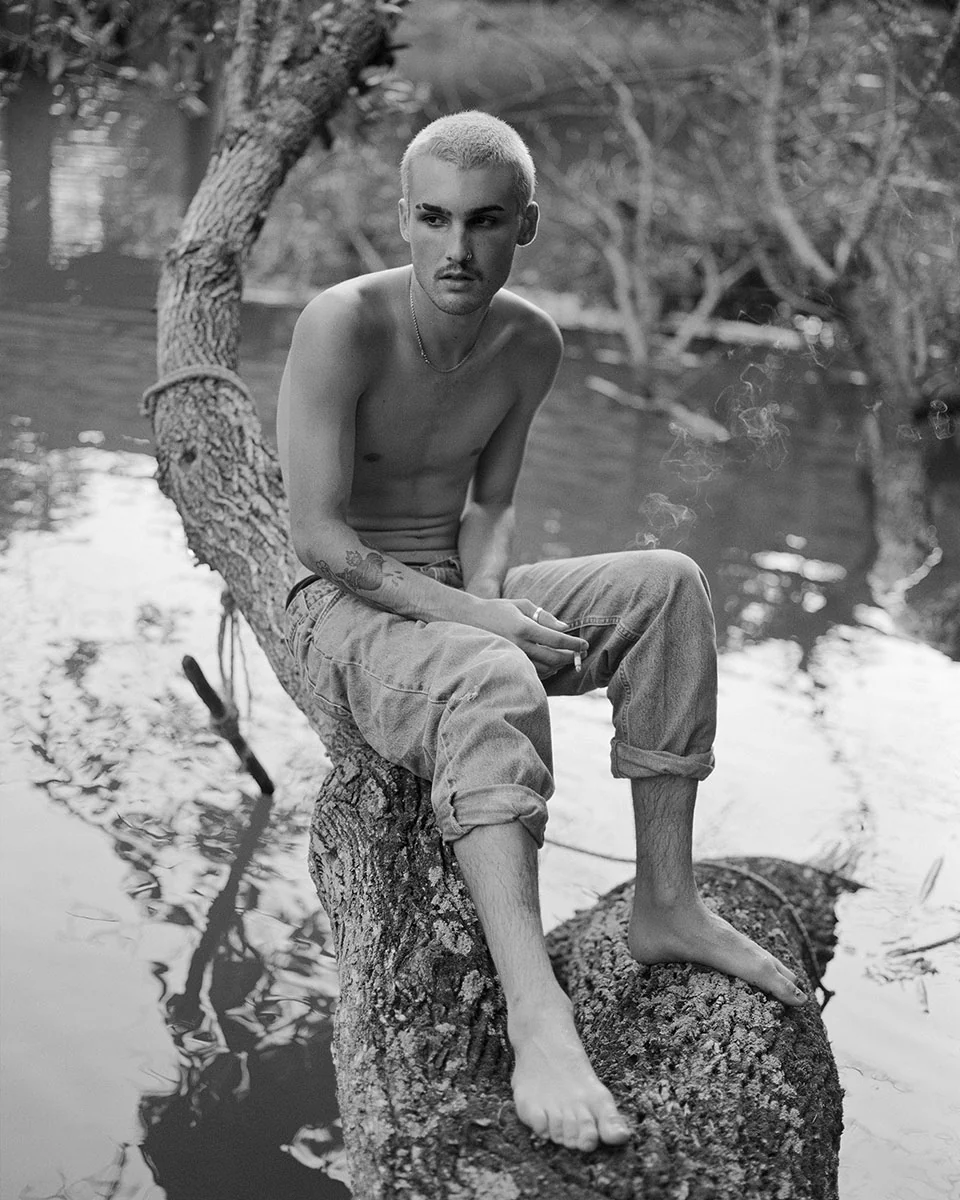

PHOTOGRAPHY

by Henry O. Head

Slow Down Crazy Child

Written by Yasemin Ozer

28/11/2025

The first wilderness we know is the one that raises us. For Henry O. Head, that wilderness was the Ozarks—limestone bluffs, cicadas, snakes, mud. Twelve Acres is his return, not to a postcard version of the past, but to the messy, unvarnished truth of it. “It’s easy for the environments you grow up in to become so familiar that you don’t even see them; they just become the backdrop to the drama of your life,” Head reflects. His photographs ask us to slow down, to recognize that what once seemed background was always the story itself.

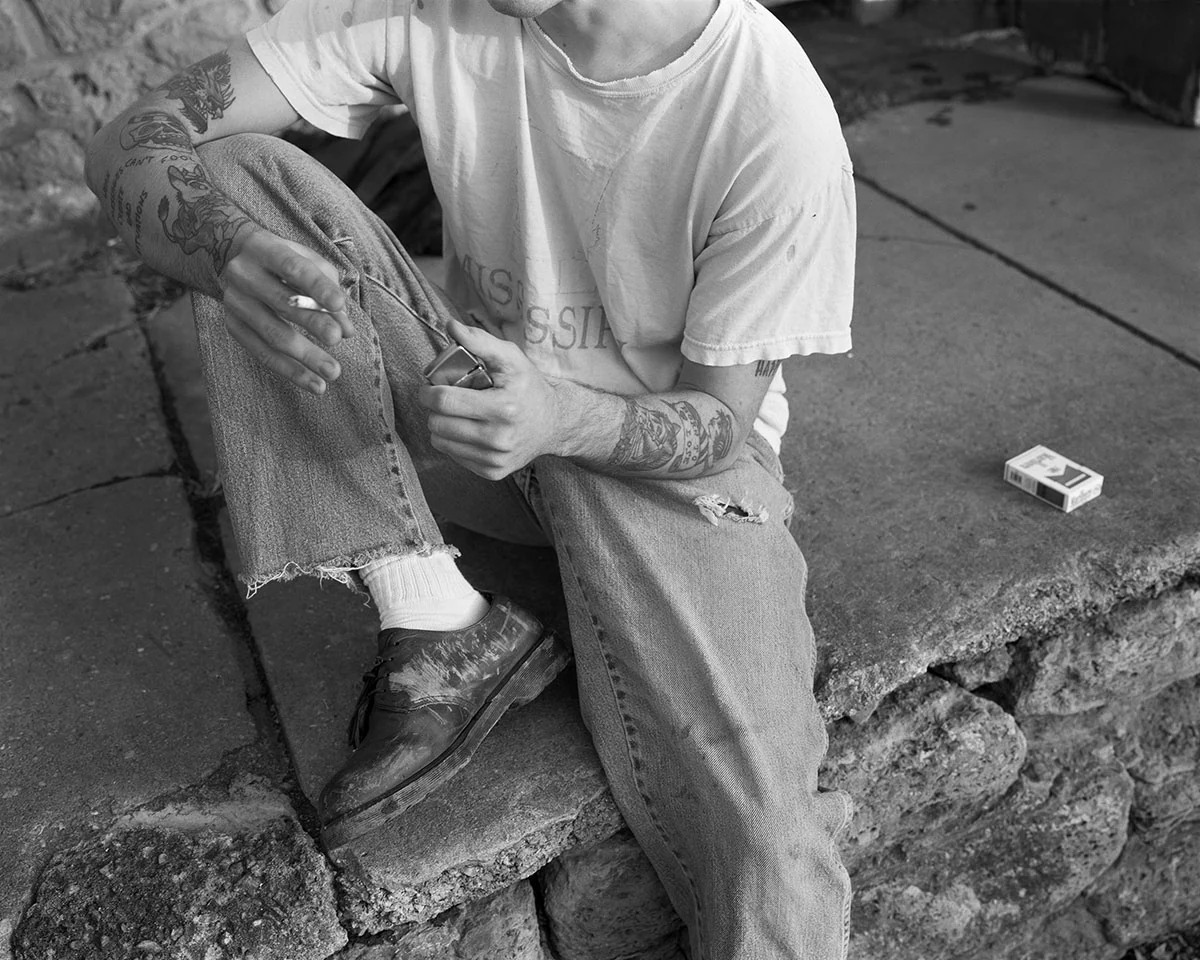

Twelve Acres is an acknowledgment that adolescence is never pristine. Head resists rose-colored memory, insisting instead on its duality: “The land has a beauty, but there’s also broken glass and snakes and all kinds of things that could hurt you.” Boyhood burns bright inside this contradiction. Boys swarm like cicadas in summer heat—explosives in open fields, sprints through thorns until blood drops like tears of joy. Yet, always, threaded alongside the danger, there is tenderness: the brush of an arm, the shadow of a laughter growing big and strong across the limestone bluffs, stretched wide by the fire’s glow, and the quiet certainty that night, however heavy or lonely, will still offer itself to your imagination.

The Ozarks are no postcard. Their beauty is not in stillness but in endurance—enduring storms, enduring companies, enduring the age-old obsession to turn every acre into profit. The fields and rivers carry their scars: barns crawling back into earth, bluffs carved for stone, creeks choked by runoff. And yet, even altered, they remain alive—restless, without a ceiling, still capable of sheltering those who return: the boys.

Through Twelve Acres, the boys lean into rivers, trees, and animals, as much as they lean into each other. A snake curling in the grass, minnows nibbling at submerged hands, a tree climbed without hesitation—each encounter blurs the line between danger and belonging, and says “I’ll take both.”

This is the paradox that pulses at the heart of Twelve Acres: wildness and safety, loyalty and loss, tenderness and recklessness. The photographs are not about preserving innocence but about allowing space for contradiction. And perhaps the truest lesson of youth is that the sting and the balm are inseparable. As Head reflects, “Boyhood… can be wild and dangerous, but still somehow it can feel safe too.”

Twelve Acres is both a plea and a reverie. A plea to pause long enough to notice what we once overlooked. A plea to fall down as the morning sun rises. A reverie that finds, in the Ozarks, not a monument to the past but a mirror of memory itself: fractured, radiant, dangerous, enduring. Still standing. Always will be.